Europe’s IT problem / How GDPR and DMA have unintended consequences

As a technologist living in the EU, specifically in Germany, it has pained me to watch my country’s and continent’s ineptitude regarding IT for the past decades. I’ve worked in several technology companies in Germany and the rest of the EU, and a common theme across large and established companies, as well as startups that I’ve worked at, is the extent to which even the technology-focused companies are stuck in the 1990s when it comes to developing software.

It feels like Europe may think it is competing in markets such as software development and SAAS,[1] but I think it really isn’t in any meaningful way—at least not in big-tech.[2]

As a result of this apparent inability to produce software platforms, such as an Operating System, or a Social Media Platform with significant relevance,[3] the EU’s market heavily relies on platforms from abroad. Most of the continent runs on Windows and Android, some of it on macOS and iOS, and practically nobody uses Linux. The popular platforms are owned, developed, and maintained by for-profit US companies.

The technology companies that supply Europe with the technological foundation it needs to function were built over decades, starting to grow to become big-tech around the 1970s—or earlier—mostly in Silicon Valley. In the 2010s, 40 years later, European politicians began to realize that the EU was entirely incapable of competing in the IT sector and started some attempts to build technology companies. Now, in the 2020s, the urgency of this “project” seems to have arrived in the minds of most politicians, but as with most things done top-down, the approach to “fix” Europe’s technology problem, is flawed and, at least for now, partially backfiring.

There are two examples I want to give, of law/regulation that was well intended but is now developing unwanted side-effects. I hope to explore ideas on how I think we might actually fix the politically manufactured tech nightmare the EU find itself in, in future posts.

Disclaimer: The following examples are what I see in my everyday life and work. I don’t expect my experience to be an objective example.

GDPR — Intent vs. Reality

GDPR Intent

A few years ago, “GDPR” (General Data Protection Regulation) was a buzzword that could rally an army of haters and an army of defenders to battle each other in heated debates. With GDPR, the intention, as far as I know, was to prohibit private espionage and force companies into disclosing what personal information they collect, which third parties they share the data with, and how they store it. GDPR also enforces secure data storage for user data and regulates entrusting this data to third parties.

GDPR Reality

I think the intention was good. For example, tracking cookies and other methods of spying on people online have to be disclosed now. At least we get to see the cookie banners asking us to accept the 896 cookies from third parties now and—in theory at least—click on a button that denies websites to use them. In practice, however, most cookie banners employ illegal practices to make everybody click the “accept”-button. And even some EU privacy officers consider “consent-paywalls” fair game now.[4]

People could sue or complain to their local data protection officers about many cookie banners currently used on European sites, but the cookie banner fatigue usually makes them click “accept” to just get rid of the annoying banners and get on with their lives. In summary, the impact of GDPR can be categorized into two main areas. One, how it impacts large internet companies, such as Meta or Google. Two, how it impacts small to medium-sized European companies.

GDPR and the big companies

GDPR mostly didn’t work regarding large internet companies, as they found ways to continue doing the same things, but differently. They still use user data to sell ads, the data has just gotten a bit worse and they now need to reconstruct more of it using the knowledge they gained before GDPR existed. What did work in regards to large companies is that GDPR requires companies doing business in the EU to disclose how and what user data they use. At least they now provide a way for users to download personal data.

GDPR regarding small businesses and EU tech companies

Regarding small to medium-sized European businesses, GDPR did have an impact, but not a good one: It scared business owners so badly, that many are still operating under the assumption that they are not allowed to do anything at all. And it felt so incomprehensible to others that they just ignore it.

On the plus side, in the EU you are now less likely to receive sensitive information as an email, and businesses made an effort to teach their employees about basic data safety. However, GDPR did not lead to the privacy revolution some enthusiasts expected. Instead of sending sensitive data via encrypted email, people reverted to sending letters or using the fax machine.

European tech companies failed to use GDPR’s momentum and popularity as free marketing to introduce more secure and private technologies—such as offering easy-to-use PGP for email.

An example from my day job

I help small businesses build their own websites. In my day-to-day work, the number one reason I see why a business has no or a very terrible website, is GDPR. Whether we, the web designers, like it or not, most businesses would be best served by a website built using a modern website builder. Sure, we like to sell expensive and technologically clean websites, but the priority of any small business should not be the technology behind their website, but its content, usability, and accessibility. Website builders such as Squarespace, Webflow, Wix, or similar are often the best choice for small businesses with limited budgets, but using them might be illegal.

All of the services above are products of US companies, run on US servers, which means most European business owners are faced with a choice. They use them, risk the fines, and have a great-looking, easy-to-use website, or don’t use them and either pay a lot more for a great-looking, easy-to-use website or have a terrible website. There is no comparable product (website builder) run by a European company on European servers, and it is not due to anti-competitive actions by the incumbents named above.

The reason there are no competitors, in my opinion, is that most small businesses go by price when deciding on the technology underpinning their website, and risk the GDPR fines. A European company, however, would have to build a competitive product and fulfill the higher and more difficult privacy standards—doing so at a competitive price compared to Webflow, Squarespace, etc. is utterly unrealistic.

What is the GDPR reality then?

GDPR set out to revolutionize privacy, and in some regards it did. There is more transparency now than before GDPR, but the practices are largely the same. Competition in the European tech industry is hampered, because it has to fulfill higher standards than the tech industry elsewhere but competes on price.

DMA — Intent vs. Reality

DMA Intent

With the DMA (Digital Markets Act), the European Commission (EC) intends to enforce a level playing field for all companies serving customers in the EU. In a nutshell, the DMA is anti-trust legislation, enforced against only a select group of companies the EU considers “gatekeepers”. Simplified, gatekeepers are platforms to which access is vital for any third party that wants to compete in the digital market. Such platforms include Apple’s iOS (the iPhone operating system), Microsoft Windows, Google Chrome, and more.

Running a platform means that you must treat third-party software products as first-class citizens on your platform. For example, Microsoft has to allow setting Google Chrome as default, and Apple has to let third parties replace the default photo app for iPhone. This is against the core philosophy of some product designers and tech executives, but it will likely help smaller companies compete with big-tech.

An aside on how the EC views Apple

I suspect that the DMA’s wording and how the EC (European Commission) applies it to Apple is partially a result of Apple’s behavior in recent years. Apple values delivering a product that is deeply integrated and just works, which means when you set up a new iPhone using an Apple ID, everything just works, including third-party email accounts you set up in Apple’s Mail app on your Mac.

However, Apple applied restrictions to iPhone that were not necessary to ensure a great user experience—in fact, some of the policies they insisted on actually harmed their users. Instead of focusing on the core value of making Apple’s products as good as possible, Apple got sidetracked by what it calls “Services Revenue” and is now in an unpleasant situation where both the EC and many developers think of Apple as their worst enemy.

Apple’s poor developer relations may have had a significant impact on how negatively the EC views Apple.

DMA Reality

It looks like the DMA has unintended side effects. It punishes companies more strongly if they have a smaller market share compared to their competitors, as the fines are based on global, not EU, revenue. And another unintended side effect is that gatekeepers have suddenly become very reluctant to bring new features to the EU market, as introducing them now poses a high risk of fines.

The fine structure leads to larger gatekeepers getting a better deal than smaller gatekeepers when breaking rules.

As with GDPR, the fines for non-compliance are based on a company’s global revenue, not its EU revenue. That means for companies like Apple, who make most of their money outside the EU, these fines are disproportionally higher relative to their market share than they are for Microsoft, which has a much larger market share. Effectively, the DMA pushes smaller gatekeepers out of the market, by punishing them relatively worse than larger gatekeepers.

For example, Apple made about $383 Billion US last year, most of it outside the EU, with an estimated EU revenue of about 7% to 14%.[5] A fine for non-compliance would be 10% of that, potentially resulting in a net loss for operating in the EU. The opposite is also true: the larger the percentage of global revenue made within the EU, the smaller the fine’s impact will be on the bottom line. This encourages gatekeepers to operate right at the edge of what they can risk with the goal of becoming a monopoly.

The ambiguity and broad reach of the DMA prevents companies from shipping new features to EU customers

This year, Apple will release some new features only to markets outside the EU, and a spokesperson confirmed that the DMA is the reason. The intent behind the DMA is to level the playing field, so why is Apple withholding some of the new flagship features for macOS, iPhone, and more from the European market? After all, these features would help it sell more iPhones, Macs, and iPads to customers inside the EU! Let’s dive into this:

Put very simply: The EU is a “spirit of the law”-region, a legal system in which the intention behind a law counts as well as its wording. This is different from the US, for example, where the “letter of the law” is what determines what is right and wrong. There are up- and downsides to either system, and I’ll avoid the philosophical debate here—for which I am not remotely qualified. The fact of the matter is, what the DMA means depends on circumstance and may change, depending on context. This introduces significant risk into the equation for gatekeepers trying to steer clear of fines.

Let’s remind ourselves, that the DMA means you must treat third-party software products as first-class citizens on your platform. For example, Microsoft has to allow setting Google Chrome as default, and Apple has to let third parties replace the default photo app for iPhone. But the DMA goes further, as it demands interoperability and interchangeability on a scale never before seen in Apple’s—or anyone else’s—products.

I’ll explain using an example

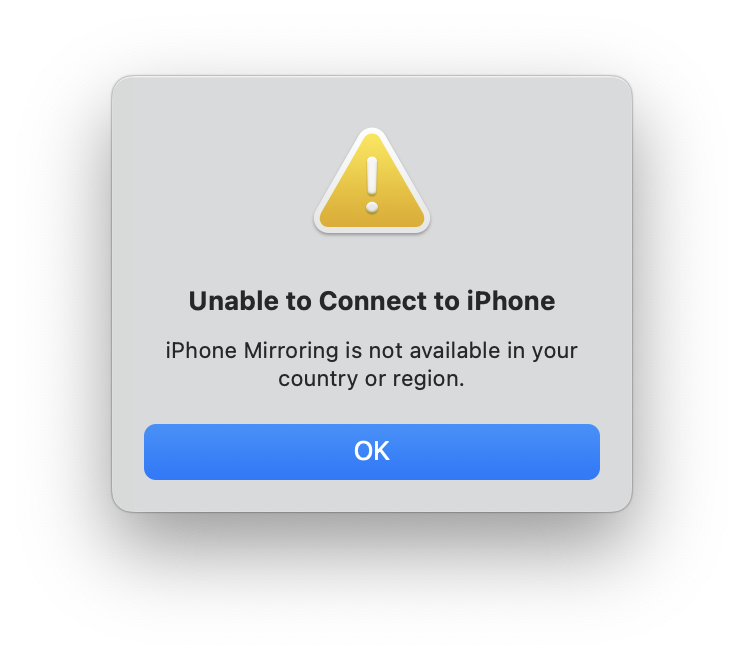

Apple will not ship iPhone and iPad Screen Sharing in the EU, and a release date for these features for the EU has not been given. Why is that?

The Screen Sharing technology is new to macOS 15 Sequoia and iPadOS 18, which will be released later this year. With this technology two main applications become possible. One, users can remotely control their iPhone via WiFi, without unlocking it, and two, users can share their screen and allow remote control between iPads. These two applications are super useful! With one you can quickly access an app on your iPhone, without having to find your phone—wherever you may have put it. With the second one, you can finally connect to your mom’s iPad when she calls you to get tech support and show her how to solve her problem—instead of explaining it over the phone.

To make these features available to users inside the EU, Apple has to enable third-party apps to do the same. That doesn’t sound too bad, does it? True, but here is the rub: New software always ships with significant technical debt. Uhm what? Technical debt, in this context, means that something might work, but the way it was programmed is far from perfect. In the case of Apple’s new screen-sharing technology, we can expect major changes “under the hood” from this version to version two.

The DMA would require Apple to make this flawed and incomplete technology available to third-party developers on day one, which is a bad idea for a thousand reasons, here are two major ones I can think of:

-

It would represent a significant security risk, as it is still a technology that is immature.

-

It would force Apple to keep this flawed version of the technology around in the future when it has already built versions two, three, or even four. Taking the first version away too quickly would then break third-party apps and harm users.

In this situation, Apple is better off not making the feature available on iPhones sold in the EU, until the technology is mature enough to open it up to third parties.

What is the DMA reality then?

With the DMA, the EU has made a tool that encourages companies to compete aggressively for market share or leave the market entirely. Any reasonable middle ground fostering cooperation has become the kill zone for any company—if they get fined.

The DMA dictates that shipping new features also means opening up the technologies that enable them to third-party developers. Doing so too early, however, is a significant security risk and adds complexity to maturing these new technologies rapidly. Not shipping a new feature is the way to go, unless a gatekeeper wants to put their users at risk and increase the development cost at the same time.

Summary

Above, I gave the example of two EU-wide legislative actions which have unwanted side effects. The EU’s Information Technology is far behind its international competition, and the top-down approach of the EU to “fix” Europe’s technology problem looks like it is backfiring. I think its time to explore how we might turn this ship around and fix the politically induced technology nightmare we are in right now—and also help Europe’s IT sector to become relevant at a bigger scale.

Update October 4, 2024:

If you’re running macOS 15, you can remote-control your iPhone, including drag & drop of files from and to it. Unfortunately, as this is a new technology that uses new APIs, the feature is not available in the EU—likely because it would require Apple to publish those APIs for third party developers while they are still in flux.

SAAS (software as a service), simply put, describes software offered not as a single purchase, but as a subscription or part of a subscription. ↩︎

Yes, of course, there are software products developed in Europe, but only one out of the seven companies classified as “gatekeepers” is from the EU as of today: Booking.com, a Dutch company. See the full list of Gatekeepers. ↩︎

Amongst us nerds, Mastodon might feel important. Compared with the numbers of Threads.net and others, however, Mastodon is a neat little nerd-fest. One that I love, but not a big-tech competitor. ↩︎

What are “consent-paywalls” and more info about them on Law StackExchange: “Can a website Demand acceptance of non-essential cookies to allow free access?” ↩︎

Apple does not disclose the revenue for the EU, but for the European region, making such calculations guesswork. Wehre on the 7% to 14% range Apple might be is unclear, but I guesstimated 12% a while back on Mastodon. ↩︎